The early cutting cycle – what the US 10yr should do

The Fed has started its rate-cutting process, so what does that mean for longer dated rates? So far the reaction is up for market rates. That’s not unusual. It likely persists for a bit. But history also shows that the 10yr yield ultimately hits a level lower than seen at the first cut. A material sub-optimal payrolls number can spark that move. Till then it’s up

History shows that the 10yr yield often rises after the first rate cut; so no surprise it has done so this time

It’s not unusual for the US market rates to rise in the period immediately after a first cut.

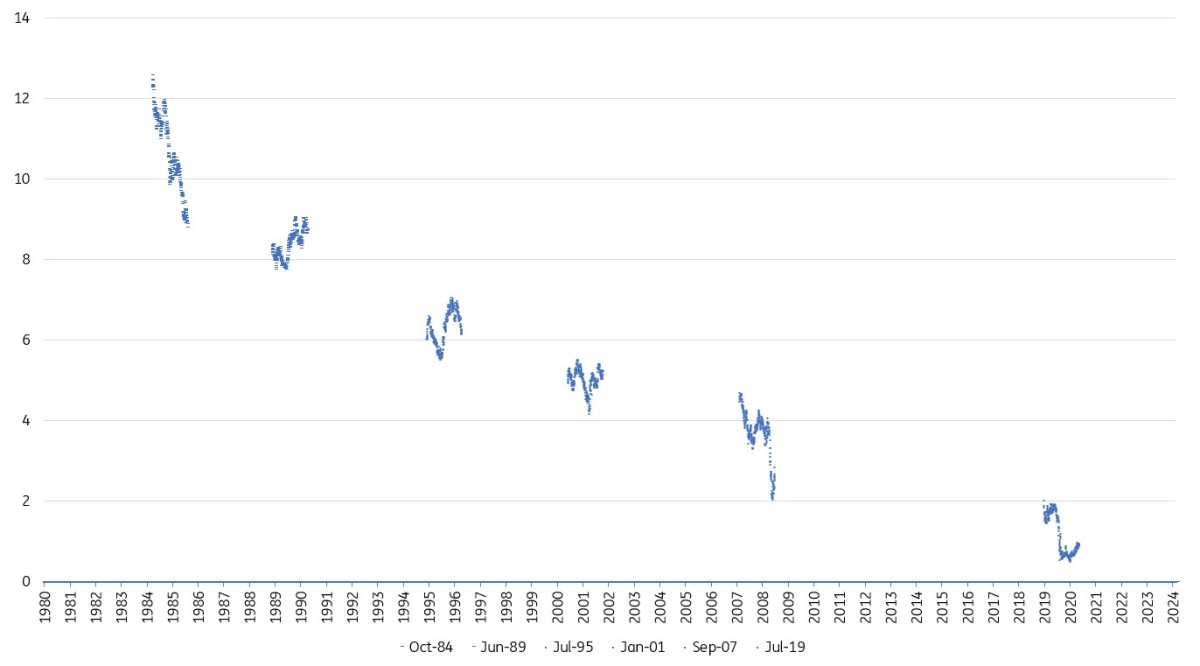

- At initiation of the four rate-cutting cycles during the 1990’s and noughties, the 10yr yield rose by 20bp to 50bp post the first cut of the cycle, typically over the following month or so.

- In contrast, the three 1980’s rate-cutting cycles saw material falls in the 10yr yield following first cuts. However, these cutting cycles were initiated from high levels of rates (in double digits, or close to). In contrast, the more modern four started with the 10yr at 6% or below (three of them were between 4.5% to 5%).

We could make the case here for extra high rate starts initiating immediate falls in the 10yr yield versus low rate starts initiating rises. But we can’t, as:

- The 2019 cutting cycle in fact saw falls in the 10yr rate (and as this was July 2019, before the pandemic was “sniffed out”; so that’s not an excuse).

Essentially the rule is, as we started out, “it’s not unusual” for market rates to rise post a first cut. So far in the current cycle, the 10yr yield is up some 10bp post the delivery of the 50bp cut on 18 September.

That now has the 10yr yield in the 3.75% area. Where now?

Here's why we should brace for further rises in the coming month

There are a number of reasons to remain tactically bearish on bonds.

Despite the chunky 50bp cut, the Federal Reserve seems convincingly upbeat on the economy. That suggests the cut is an offensive one; a means to averting a material slowdown. If true, it suggests that recession risk is reduced (not panic increased). If so, there should be no need for the Federal Reserve to take the funds rate below 3%. If true, it places a red line floor at c.3% for all rates right out the curve (theory that inversion is no equilibrium).

What about the 10yr Treasury yield? Remember, SOFR is the risk free rate. Extrapolation of the funds rate manifests in a SOFR curve. Treasuries sit above that (by 50bp). That gives an implied floor of c.3.5% for the 10yr yield. The current 10yr yield of 3.75% sits just 25bp above that. Of course Treasury yields can find a reason to re-break down towards 3.5%. But that reason is not here, yet. Hence the path of least resistance is still higher.

We’d argue there is a viable path to 3.9% for the 10yr yield for starters. That would equate to a c.35bp backup in the 10yr yield post the 50bp cut; certainly, within the margin seen during previous backup periods.

The big call then is whether there is an appetite to break above 4%.

The 10yr and Fed cutting cycles (the six major ones since 1980)

Chart shows the 10yr yield from the moment the Fed cuts, and the subsequent 18 months...

And here's why the 10yr yield should in the end take out its pre-rate-cut low

Previous cycles show that a month to a quarter after the first cut there tends to be confirmation from the data that things are not great, and if anything is getting worse. That tends to expose the upside move in yields to the new reality that the Federal Reserve still has considerable work to do. It results in a leg lower in yields, and leads to the basic truism of most previous cycles – even if yields initially back up, they ultimately fall back down again, and typically to much lower levels to where they were at the moment the Fed initiated their cuts, as can be gleaned from the chart above. That’s the strongest argument against the notion that a material break above 4% is likely.

That said, we still need the excuse to break the back-up trend in yields. We’d suggest that the most likely excuse is to come from the employment report. Sure we’ll watch GDP and retail sales and production and the weekly claims among others. But in the end, we assert it’s all about payrolls.

The key level there is 150k – the replacement level. Once we go below that (and we have already) the unemployment rate tends to rise. In fact, four of the last five readings have been below 150k. The key issue here is how far below 150k is impactful enough for the 10yr yield to about turn. A negative print would be enough. But a reading in the zero to 50k area could also be enough, being statistical-error-wise close enough to zero.

Something like that can spark the next move lower in the 10yr yield. And then we are on a journey back down towards the 3.5% area, taking out the prior low in the 3.6% area. That would be enough to complete the narrative that the 10yr yield tends to get to a new low post the first cut, even if it pops higher for a bit initially. This remains our central thesis for the remaining months of 2024.

What about 2025? See more here on our rationale for a medium test of the 4.5% (to 5%) area for the 10yr yield. For 2024, its 3.9% next for the 10yr yield, then a think about 4%. Which ultimately fails, and we revert back down towards 3.5%. A dip below that makes little fair value sense if the forward view for the Fed is they don't break below c.3%. Subtract 50bp from each of these to get what it means for 10yr SOFR.

Download

Download opinion

Padhraic Garvey, CFA

Padhraic Garvey is the Regional Head of Research, Americas. He's based in New York. His brief spans both developed and emerging markets and he specialises in global rates and macro relative value. He worked for Cambridge Econometrics and ABN Amro before joining ING. He holds a Masters degree in Economics from University College Dublin and is a CFA charterholder.

Padhraic Garvey, CFA

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more