The threat to world trade from Covid-19 subsidies

Governments worldwide have implemented subsidies to rescue their economies from the effects of Covid-19. These measures provide essential support to firms. But we're looking at an uneven playing field as some also risk distorting and reducing world trade should they remain in place

Essential support in a crisis

Governments worldwide have implemented subsidies as part of their responses to Covid-19, to bridge the drop in demand caused by lockdowns and continued social distancing. In total, additional spending and foregone revenue in G20 countries are equivalent to 6% of their combined GDP. Another 6% has been injected to boost liquidity through loans, equity and guarantees.

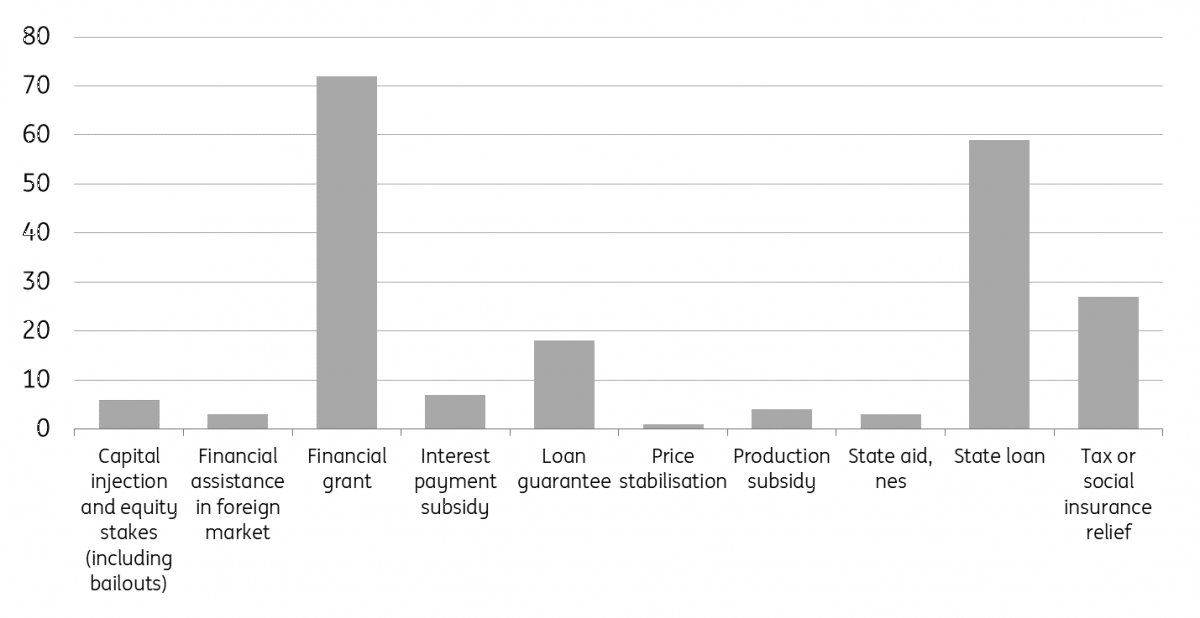

Global Trade Alert records more than 200 different subsidies granted since March 2020, as you can see below. The most-used form of support has been financial grants, including the EU Commission’s expansion of its Temporary Framework to allow financial support schemes. State loans and tax relief schemes have also been introduced in many countries with different target groups, often SMEs or firms in a particular region.

Governments have intervened in many different ways to fight the economic effects of the virus

The EU’s Temporary Framework is a time-limited measure, which will run until December 2020 unless a further extension is agreed. However, two-thirds of the new subsidies have no end date. With this comes the risk that the subsidies introduced in the wake of Covid-19 open the door to negative long-term effects.

The trouble with subsidies

State support has been essential to keep firms going and avoid a devastating economic collapse. But the experience of the financial crisis showed that subsidies can have negative long-term consequences which play out through international trade flows.

Subsidies can have negative long-term consequences

Subsidies act as a barrier to trade by reducing some firms’ costs, which allows them to sell their goods for lower prices than their competitors without necessarily being more efficient or productive. Subsidies can also suppress demand for imports by enabling firms to afford higher-priced domestically-produced goods instead of cheaper imported goods and services.

In whichever form they take, subsidies risk giving an advantage to less efficient producers at the expense of more efficient ones. Over the long term, this can lead to lower productivity growth in the country implementing the subsidy. Subsidised industries may also lead to excess capacity and ‘dumping’ of goods on international markets, which damages exporters’ prospects in other countries.

A silent trade war?

Not all subsidies will have an impact on international trade. Consumer services such as hairdressing and cultural activities have been particularly affected by lockdowns and ongoing social distancing measures. Where subsidies are targeted towards these industries, the risks to international trade are low.

However, Global Trade Alert identifies thousands of traded products which are affected by new subsidies, around 3% of world trade in total. This is similar to the share of trade affected by the US-China trade war. Based on the effects of subsidies introduced in the financial crisis, the potential hit to trade is similar to the net losses to date from the trade war between the US and China,

Subsidies affect as much trade as the trade war and could cause a similar hit

Another headwind for world trade

Subsidies won’t heap additional damaging uncertainty on the global economy in the way that the trade war has done. But worryingly for the global recovery from Covid-19, the effects of newly introduced subsidies fall most heavily on the engines of world trade growth, with emerging economy exports making up 60% of the flows affected.

As export-orientated economies, a recovery in exports is vital for these countries’ recoveries, as well as world trade overall. This is especially the case following the capital outflows from emerging economies which happened at the beginning of the pandemic. Until these flows return, cancelled investment projects will leave domestic demand subdued, so export growth is needed to pick up the slack.

Governments’ efforts to support their economies won’t all affect world trade, especially where subsidies are targeted towards the activities that make little use of traded goods. But some measures risk creating another headwind for international trade, especially because most of the support is currently open-ended.

Download

Download article

11 September 2020

Brexit, the pound, and the ECB’s possibly risky verbal balancing act This bundle contains 7 articles"THINK Outside" is a collection of specially commissioned content from third-party sources, such as economic think-tanks and academic institutions, that ING deems reliable and from non-research departments within ING. ING Bank N.V. ("ING") uses these sources to expand the range of opinions you can find on the THINK website. Some of these sources are not the property of or managed by ING, and therefore ING cannot always guarantee the correctness, completeness, actuality and quality of such sources, nor the availability at any given time of the data and information provided, and ING cannot accept any liability in this respect, insofar as this is permissible pursuant to the applicable laws and regulations.

This publication does not necessarily reflect the ING house view. This publication has been prepared solely for information purposes without regard to any particular user's investment objectives, financial situation, or means. The information in the publication is not an investment recommendation and it is not investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Reasonable care has been taken to ensure that this publication is not untrue or misleading when published, but ING does not represent that it is accurate or complete. ING does not accept any liability for any direct, indirect or consequential loss arising from any use of this publication. Unless otherwise stated, any views, forecasts, or estimates are solely those of the author(s), as of the date of the publication and are subject to change without notice.

The distribution of this publication may be restricted by law or regulation in different jurisdictions and persons into whose possession this publication comes should inform themselves about, and observe, such restrictions.

Copyright and database rights protection exists in this report and it may not be reproduced, distributed or published by any person for any purpose without the prior express consent of ING. All rights are reserved.

ING Bank N.V. is authorised by the Dutch Central Bank and supervised by the European Central Bank (ECB), the Dutch Central Bank (DNB) and the Dutch Authority for the Financial Markets (AFM). ING Bank N.V. is incorporated in the Netherlands (Trade Register no. 33031431 Amsterdam).