What weak bank lending and strong deposit inflows mean for the ECB

Bank lending growth dynamics continue to diverge between countries, while strong deposit inflows put increasing pressure on bank interest margins

Bank lending to business remains strong only in Italy

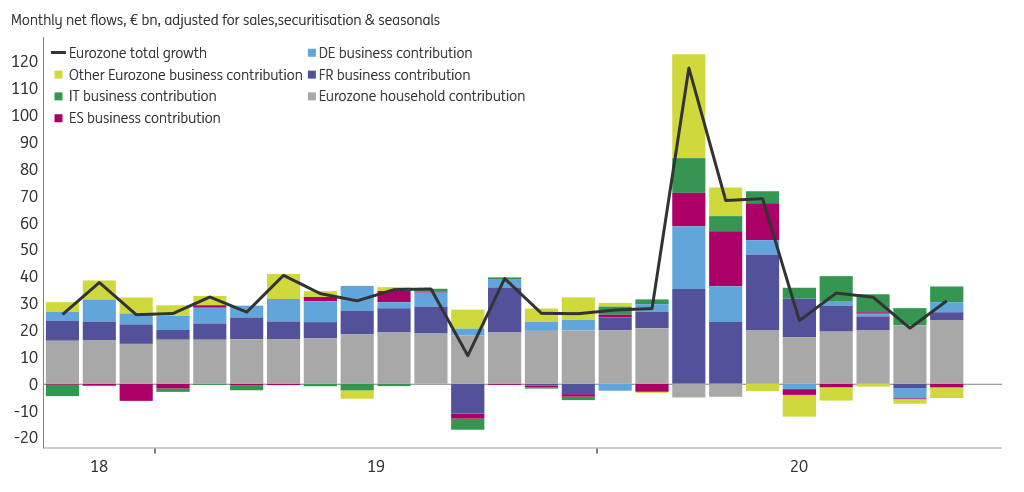

Today’s October ECB monetary data shows that bank deposit inflows remain elevated, while net bank lending to businesses was weak in most countries. Lending to households has been holding up well this year, while business lending has understandably displayed large fluctuations. In fact, net bank lending to businesses has been around zero or even negative since the summer in most countries. France and Italy stand out though.

In Italy, businesses continue to borrow heavily from banks

In France, net bank lending to business was very strong and remained so for longer than elsewhere, only dipping below zero in September and slightly recovering in October. In Italy, businesses have continued to borrow heavily from banks, with only a slight deceleration visible over the past few months. It shows in the substantial contribution of Italian business lending to the eurozone total in the chart below.

Eurozone bank lending to households and non-financial businesses

It is interesting to note that in the ECB Survey of Access to Finance of Enterprises, published this Tuesday, SMEs in Italy and the Netherlands were the least pessimistic about the expected availability of finance (see our coverage), likely for very different reasons.

SMEs in Italy and the Netherlands are least pessimistic, but for very different reasons

Italian businesses appear confident that bank facilities remain available to them, and indeed lending data proves them right so far. The relative optimism of Dutch businesses on the other hand can be explained by the fact that, on average, they have much lower financing needs in the first place, no doubt helped by direct grants and tax credit extended by the government. Dutch government support is provided less via government guaranteed loans compared to some other countries. Consequently, business demand for bank lending has been low in the Netherlands, translating into net negative bank lending there.

Most countries on track to meet TLTRO benchmark, but not all

Which brings us to the implications of today’s figures for banks' prospects of attaining the TLTRO benchmark. In order to qualify for the most attractive TLTRO-III borrowing rate of -1% between June this year and next, banks would need to exceed their lending benchmark (0% in most cases) in the “special reference period”, which is the 13-month period running until the end of March 2021. Banks in France, Spain and Italy are showing the strongest lending growth so far and are very well positioned to obtain the most attractive TLTRO-III lending rates. Net interest income of banks in these countries may get substantial support from the very attractive TLTRO lending rate. Realising the most attractive -1% TLTRO lending rate in Belgium and the Netherlands is becoming increasingly challenging.

Cumulative TLTRO-eligible net lending growth since March '20, %

Apart from the “special reference period”, the ECB has also set a longer-running “second reference period”. The picture is little different there however, with the Netherlands now at the benchmark and trending down, while most other countries remain above. For Benelux banks, realising the -1% rate may prove difficult even though we note that bank-to-bank differences may be substantial. Apart from weak business lending demand, some Dutch banks are in the process of driving down parts of their lending books as part of larger strategic shifts reflected as downward pressure in loan books.

Meeting none of the TLTRO benchmarks would probably lead to prepaying of TLTRO funds

Meeting none of the lending benchmarks means that a bank would, after the special interest rate period ends, face its TLTRO rate rising from -0.5% to 0%. In most countries this would mean, in our view, that that the bank in question will look into prepaying the funds early, i.e. for the first five tranches in September 2021.

High deposit inflow causes another headache for banks

While bank lending has decelerated since the summer, the inflow of bank deposits has held up. This poses a problem for banks: with little bank lending volume generated, the excess deposit inflow will have to be “parked” at the ECB at a marginal -50bp in many cases. In fact, since March this year, for every additional euro parked at a bank, on average only 40 cents is lent to businesses and households.

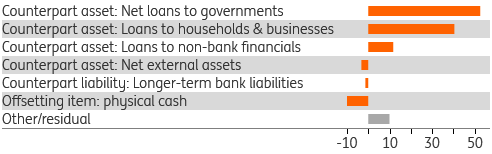

Counterpart items to bank deposit increase since March '20 (%)

Monetary geeks and accounting fans may wonder: how is this at all possible? How can deposit inflow remain high while net bank lending has come down? From a monetary perspective, aren't deposits in fact created by lending? Indeed most money is normally created by commercial banks' lending. However, the word “normal” ceased to apply to monetary dynamics some time ago. Since the ECB started quantitative easing, it opened a new channel of money creation. In fact 40% of the deposit inflows in the years 2015-2019 find their origin, not in commercial bank lending but in Eurosystem government bond buying. This ECB-government channel has become even more important since March this year.

| 53% |

of the €995bn of new bank deposit inflows since March can be attributed to Eurosystem government bond buying |

Eurozone governments have been borrowing heavily, issuing bonds that have by and large been bought (on the secondary market) by the Eurosystem. Governments have passed on the money thus created directly to businesses and households. As such, since March, 53% of the €995bn of new bank deposit inflows can be attributed to Eurosystem government bond buying. From a commercial bank perspective, these increased liabilities are not matched by asset generation (the bonds move onto the Eurosystem’s balance sheet), and hence the funds end up at the Eurosystem, eating away at the banks’ interest margin.

Implications for the 10 December ECB meeting

Given the second lockdown, the ECB is widely expected to provide additional monetary stimulus at its forthcoming meeting. Zooming in on the TLTRO-III, the ECB could look into extending the programme by providing additional tranches on top of the two that are still left in December 2020 and in March 2021. This would provide banks with additional cheap funding at longer maturities to make sure the ECB’s monetary policy does not tighten prematurely. On top of that, the central bank could look at closing the gap between the end of the special interest rate period (June 2021) and the first prepayment date (September 2021), by lengthening the special interest rate period. This would ensure that TLTRO-III participation does not prove too punishing for banks that face a lack of lending demand in their geographic areas due a combination of relatively strong company fundamentals, design of government support frameworks and a longer-running deleveraging trend. A change in the lending benchmark calculation could be another alternative to better accommodate such factors.

To ease some of the additional pressure from increasing deposits caused by the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme and Asset Purchase Programme (even more so if these programmes are expanded), the ECB could adapt the existing deposit tiering system, allowing a larger share of central bank deposits at 0% instead of at the deposit rate of -0.5%.

Download

Download article

27 November 2020

Reasons to be cheerful, part 3 This bundle contains 6 articlesThis publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more