Three scenarios for Brexit under Boris Johnson

A new eurosceptic UK prime minister will face stiff opposition from Parliament if they push for a 'no deal' Brexit. That might lead to another Article 50 extension if the new leader applies for more time to break the deadlock. But one way or another, the probability of a general election is rising

Five scenarios for Brexit under a new leader

What would a 'Boris Brexit' really look like?

Former UK foreign secretary Boris Johnson is now odds-on to replace Theresa May as Conservative leader. But what would a 'Boris Brexit' really look like?

Markets, at least, have become warier that it could result in a ‘no deal’ Brexit. In the first instance though, we assume that the first act of any new leader will be to return to Brussels and at least attempt to renegotiate the current deal.

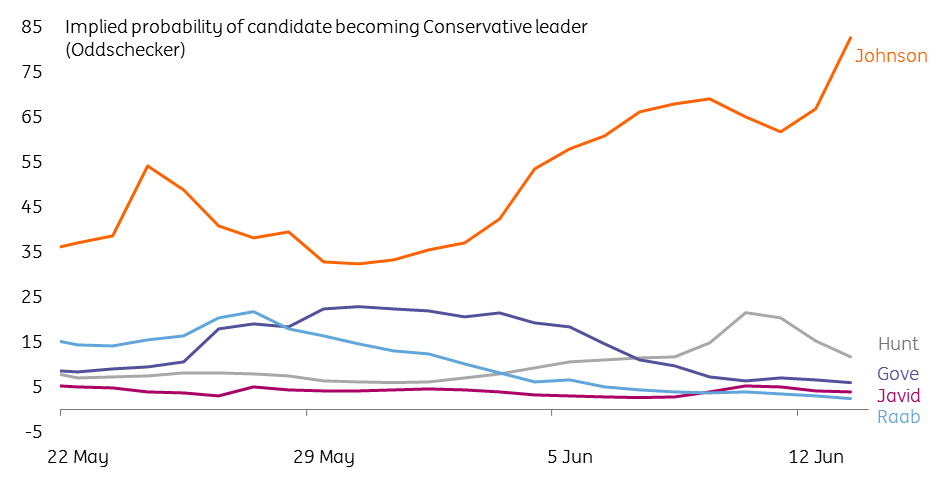

Johnson is easily the favourite to become leader

Some candidates have gone one step further by saying they would try to seek a Parliamentary majority for an adapted deal upfront – e.g. one that adds a time-limit on the Irish backstop – to try and demonstrate to the EU that they have the necessary support to get their vision ratified at home.

In reality, it’s very unlikely that a new leader will be able to achieve something Theresa May could not. The EU has been extremely clear that is not prepared to reopen negotiations on the withdrawal agreement, which includes the controversial Irish backstop.

But what would happen then? Taken at face value, recent comments from Johnson and other Eurosceptic candidates suggest they want the UK to leave in October, whether a deal is in place or not.

If a new PM did push for ‘no-deal’, Parliament would likely do all it can to stop it from happening. But unlike in earlier in the year, there may be few legislative mechanisms available to do so (for more, see this Institute for Government report). That’s partly why we think the probability of MPs stepping in and revoking Article 50 is still only around 5%.

Having said that, we think the risk of ‘no deal’ is still relatively low (20% probability) and we think there are three main alternative scenarios that could prevail instead.

Scenario 1: Parliament forces an election through no confidence vote (35%)

While the legislative options may be limited, there is one obvious way that Parliament could block ‘no deal’, and that’s to try and force a general election. The leader of the opposition, Jeremy Corbyn, could put forward a motion of ‘no confidence’, and it wouldn’t take many Conservative MPs to back it. Several moderate Conservative lawmakers have hinted they would be prepared to collapse their own government if that was the only way of stopping ‘no deal’.

A no-confidence motion is unlikely to be successful unless ‘no deal’ is truly imminent

This poses two questions: when could an election happen, and what would be the result? On the former, the minimum time between a successful no-confidence vote to election day is seven weeks. The first opportunity for a confidence vote would be at the start of September when MPs return after the summer, which could allow just enough time to hold an election before the end of October.

In reality though, a no-confidence motion is unlikely to be successful unless ‘no deal’ is truly imminent. That suggests that if an election happens, it's unlikely to be triggered until mid/late October, and therefore wouldn’t take place until late November/December at the earliest. Another Article 50 extension would be needed, although it’s unlikely the EU would try to block it in this scenario.

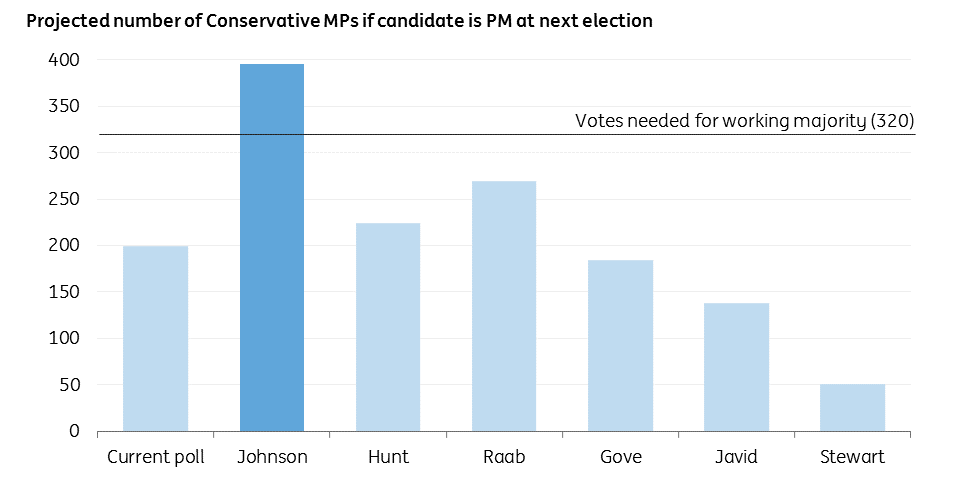

Calling the winner of a late-2019 election is much trickier. A simple mapping of recent polling onto the UK’s electoral system suggests Boris Johnson could hypothetically secure an absolute majority for the party at the next election (Figure 2). But that prediction comes with several caveats (electoral calculators can be relatively crude), and an election forced upon him by Parliament could prove very tricky for the Conservatives. A failure to live up to his promise of achieving Brexit by October would undoubtedly give leverage to the Brexit Party.

A lot would also depend on Labour’s Brexit position - so far leader Jeremy Corbyn has been reluctant to back a second referendum. But polls suggest that if he is to become prime minister, he would need to join forces with several other political parties – almost all of which would set a second referendum as their price for a coalition/confidence and supply arrangement with Labour.

It’s not impossible therefore that Labour opts to campaign for a second referendum from the start, to try to limit losses to other remain-supporting parties.

Polls suggest Johnson would be the best candidate for the Conservatives at an election – but that could change…

Scenario 2: ‘Revamped deal’ receives Parliament’s backing (25%)

The upshot is that there is a clear risk that a new leader could be knocked out of power if they try to push for ‘no deal’. This begs the question: would Boris Johnson (or an alternative Eurosceptic candidate) be more pragmatic in office than current rhetoric suggests?

On the face of it, this sounds unlikely. Mr Johnson said at his campaign launch that “we must do better than the current withdrawal agreement”, but as we noted above, meaningful changes are unlikely to be forthcoming.

But assuming Boris Johnson and other leading Brexiteers believe the election threat to be credible, it's not impossible that they'll be more open to approving May’s deal (with cosmetic tweaks) than it currently seems. Don’t forget that in the third meaningful vote back in March, a number of leading pro-Brexit Conservatives actually voted for May’s deal – something that was unthinkable just weeks before - on the basis that they would have a ‘true Brexiteer’ in Number 10 for the next phase of trade talks.

That’s not to say it will be easy to get a stable majority for the deal. There are a handful of MPs who want nothing short of ‘no deal’, while concern within the more moderate factions of the party could increase. It also seems unlikely that the DUP would sign up to a deal with the backstop. We, therefore, think this scenario is relatively unlikely, and if Boris fails to get Parliament fully on-board, he could quickly revert back to pushing for a ‘no deal’ exit.

Scenario 3: The wildcard - Johnson backs a second referendum (15%)

Ultimately, a new leader may well conclude that the current deal is just as unpalatable as the risk of a ‘general election’. So what about a second referendum?

On the face of it, it sounds unthinkable that a Brexiteer prime minister could decide to initiate a second referendum. However, according to the Eurasia Group, Johnson may be more open to this option than he admits publically.

This would undoubtedly be a high-risk strategy. While Boris Johnson would presumably push for a remain vs. no deal vote to try and maximise the leave share of the vote and gain a mandate for a harder vision of Brexit, Parliament could force a different choice of referendum question into the legislation, or even block it all together – perhaps culminating in an election after all. A botched referendum attempt, where either it took too long to arrange, or where ‘Remain’ won, would spell disaster for the Conservatives at the ballot box.

We, therefore, think it’s unlikely a Eurosceptic prime minister would go down this route – and as we mentioned earlier, we think the legislative options for Parliament to force a second referendum upon the government are fairly limited. We currently put a 15% probability on one being triggered before October.

Lesser of two evils: Losing power vs losing a hard Brexit

The bottom line is that a new prime minister could easily find themselves boxed in by the same hurdles as Theresa May. Ironically, this means there is also a fairly good chance that a new leader will try and kick the can down the road for another six months, to allow more time to break the deadlock. There are question marks over whether the EU would grant more time without justification (France, in particular, is reluctant to allow further extensions), but even if they did, the leader will still arrive back at the same scenarios further down the road.

A new prime minister could easily find themselves boxed in by the same hurdles as Theresa May

In the end, it will come down to whether the new prime minister is prepared to risk losing a ‘no deal’ Brexit, in order to retain power and control of the next stage of negotiations. Taking recent comments from the leadership contenders at face value, we think there is a reasonable chance that a new Eurosceptic leader will attempt to push for a ‘no deal’ Brexit if they are unable to rework the deal before the end of October. That leaves a general election as the most likely scenario out of the ones we’ve considered, but a more pragmatic approach certainly shouldn’t be ruled out either.

For the time being, the uncertainty surrounding the process will continue to restrict economic growth. As a result, we do not think the Bank of England will hike interest rates this year, particularly given the broader risks to global growth.

Download

Download article

17 June 2019

What’s happening in Australia and the rest of the world? This bundle contains 10 articlesThis publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more