Switzerland: Why too little debt could be a problem

In the European Union, high debt levels are a constant concern. But Switzerland faces the opposite problem and, paradoxically, it could be missing out on extra revenue as a result

General government debt level (% GDP) in Switzerland and advanced economies

Very low debt

Switzerland is an exception when analysing the level of its debt. Gross public debt was equivalent to 41.8% of GDP in 2017, according to the IMF, of which 14.5% of GDP is borne by the federal state (Confederation) and the remainder by the cantons. This is the lowest level of public debt in Switzerland since 1991 and is well below the average debt level of the EU (83.3% of GDP) or the euro area (89.1% of GDP). While other OECD countries have tended to increase their debt as a proportion of their GDP in recent years, Switzerland has seen its debt decrease every year.

This decrease in debt follows a succession of budget surpluses in previous years. The budget balance since 2006 has been positive almost every year (except in 2013 and 2014). For 2019, the Confederation's budget could lead to a surplus of 1.3 billion francs (at least). More surprisingly, the Swiss Confederation ends each year with a larger budget surplus than expected at the beginning of the year in the budget. For example, in 2018, the Swiss Confederation recorded a budget surplus of 2.94 billion francs, ten times more than expected, thanks to tax revenues which exceeded expectations, while spending remained under control. Since 2007, only the 2014 financial year closed with a result slightly below the budget forecasts.

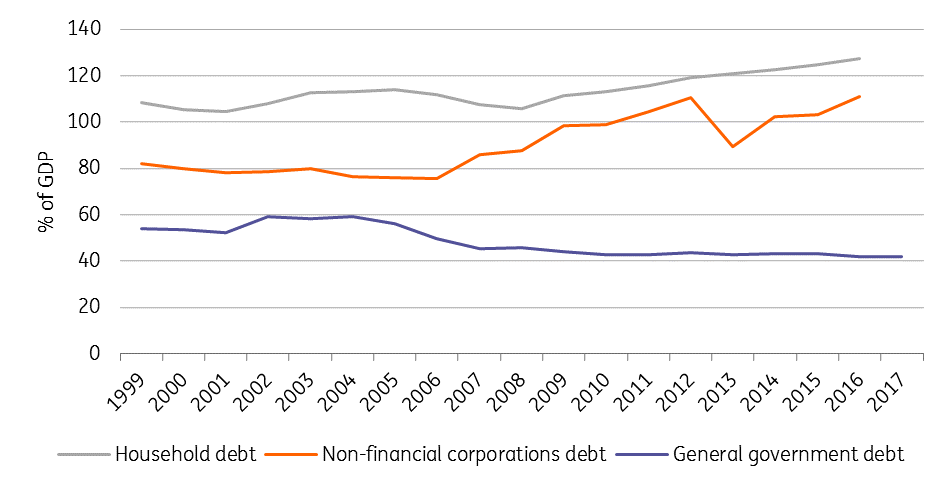

To be sure, however, private debt (and especially household debt) is higher than in most OECD countries.

General government, household and non-financial corporations’ debt level (% GDP) in Switzerland

A debt brake in the constitution

The main cause of Switzerland's low indebtedness is a mechanism introduced by the Confederation to stabilise the federal debt: "the debt brake". Enabled in the Constitution since 2003, with a population approval rate of 85% in 2001, the rule has strong legitimacy and many cantons have introduced similar models. The principle: public spending should not exceed revenues over a full economic cycle. The formula allows for a deficit during a recession, offset by surpluses during an expansion period.

However, the implementation of this system has resulted in a significant debt reduction, rather than just stabilisation. This is because the rule is applied asymmetrically and expenditure tends to be overestimated each year, while revenue is systematically underestimated. Almost every year since the beginning of this system, federal authorities have missed their goal by overestimating expenditures or underestimating revenues.

Switzerland is paid to go into debt

This mechanism is largely supported by the Swiss population and illustrates a certain mentality which considers that debt is bad and that it is necessary to reduce debt as much as possible. Each year, the government uses the budget surplus to reduce the debt pile, which leads to a progressive deleveraging of the Swiss public authorities.

Nevertheless, this run of deleveraging poses major questions of economic policies, given current market conditions. Indeed, deleveraging implies a reduction in the supply of Swiss government bonds. However, Swiss debt is considered by the markets to be extremely safe and the demand for these securities is huge, especially when conditions lead to a "flight to safety". The consequence of this strong demand and weak offer is that interest rates on Swiss debt are extremely low, the lowest in the world. The Swiss Confederation borrows with an interest rate of -0.31% at 10 years, -0.62% at 5 years, -0.02% at 15 years. Only state bonds with a maturity of 20 years or more imply a positive interest rate for the Confederation. With these (strongly) negative rates, the Swiss state is actually paid to go into debt. The paradox is there: by reducing its debt, Switzerland is missing out on budget revenues.

Time to change?

According to some experts and academics, Switzerland's strategy of deleveraging is excessive and should stop. For example, Professor Philippe Bacchetta (University of Lausanne) believes that Switzerland is experiencing the "curse of regional suppliers of safe assets". According to him, given the global shortage of safe assets, global demand for liquid assets is being channelled to safer countries (including Switzerland as a first preference) that can offer such assets. These countries are experiencing capital inflows and upward pressure on their currencies. He therefore believes that additional indebtedness could reduce the upward pressure on the Swiss franc and thus relieve monetary policy.

The IMF has similarly endorsed these conclusions for Article IV Consultations in recent years.

- In 2016, the IMF wrote "Given the available fiscal space and constraints on monetary policy, Directors saw scope for additional fiscal support, including by fully utilising the room available under the existing debt brake framework.”

- In 2018, the IMF became more insistent saying, “Given constraints on monetary policy, most Directors encouraged the authorities to adopt a balanced structural position by utilising the available fiscal space, which would allow for a more balanced mix of macroeconomic policies in support of domestic demand, facilitating the reduction of the high current account surplus”.

- In 2017, the IMF suggested revising the debt brake rule to make it more symmetrical and dependent on debt levels: “A symmetric rule would also support a better macroeconomic policy mix—with a somewhat looser fiscal policy and a less accommodative monetary policy—in order to relieve pressure on monetary policy tools during periods of low inflation. In addition, as currently specified, the rule is independent of the level of public debt. Consideration could be given to allowing a larger (smaller) countercyclical response when debt is below (above) long-term sustainable levels.“

Monetary policy in Switzerland is currently extremely accommodative, with a negative interest rate (-0.75%) and interventions on the foreign exchange market to weaken the currency when necessary. Despite a very accommodative policy, price stability remains a major challenge for the SNB, inflation remains very low and the risks of deflation have never been averted (in the last 10 years, annual inflation has been negative for six years ). Given the global economic context, we believe that the SNB will not be able to raise rates for several years. Against this backdrop, the room for manoeuver of monetary policy to fight against a possible future recession is very thin. It seems, therefore, that calls for a less restrictive fiscal policy and a more appropriate policy mix will grow louder.

For now, however, the debate has not reached the political level in Switzerland. As long as every budget is well debated and parties have their own priorities for spending, the debt brake rule doesn't seem to be in question. Indeed, every budget surplus is greeted with a self-congratulatory round of applause on the sound management of public finances, rather than an introspective look at how things could potentially be even better under a different system. Still, there are some signs that the debate could gain momentum in the coming months and years. For example, the Federal Department of Finance has decided to look into the matter and a report is expected by the end of March 2019. To be continued....

Download

Download article22 March 2019

In case you missed it: Central banks take a U-turn This bundle contains {bundle_entries}{/bundle_entries} articlesThis publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more