Supply chain issues are here to stay

As global demand improves and continues to support industrial production, we think supply chain problems are here to stay, making it difficult and expensive for firms to get hold of industrial inputs even as more countries recover from the pandemic, particularly in a policy environment increasingly geared towards reshoring and domestic production

Volatility and uncertainty in supply chains

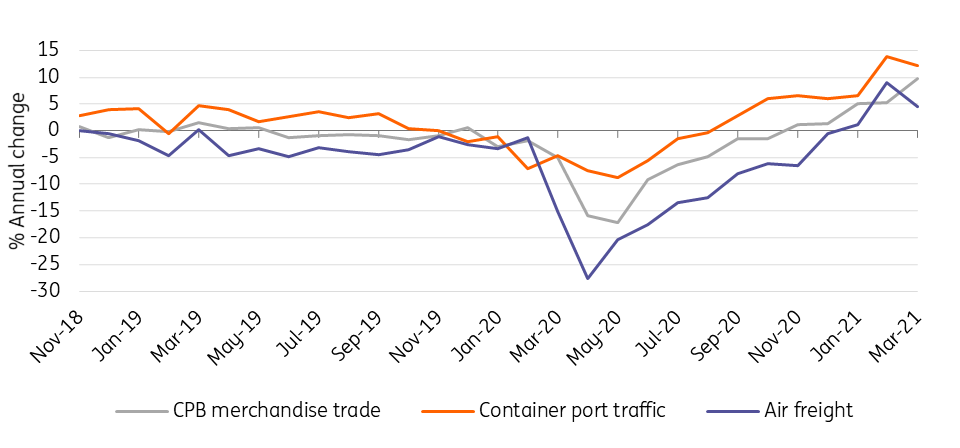

During the pandemic, world trade in goods has benefited from the global recovery in retail sales and industrial production, while other sectors remain much harder-hit by lockdowns and uncertainty, so much so that global trade’s recovery has outpaced global GDP. Ocean freight, normally responsible for the bulk of world goods trade, has had to compensate for reductions in air freight capacity while passenger travel remains restricted.

Ocean freight has become even more important, putting all capacity under pressure

Global trade in goods and different freight types, annual growth

But the positive picture from world trade volumes has come with supply chain volatility and uncertainty. Trade volumes have bounced back after lockdowns at ports, as well as the blockage of the Suez canal, but supply chain disruptions have accumulated and worsened. With some inputs taking much longer to be delivered, and containers becoming displaced, each setback is causing shortages of inputs and price increases to become more acute.

The faltering of supply chains is partly because of the strange effects that the pandemic has had on global economies. Even as demand for goods overall has remained strong, the stop-start nature of different recoveries has disrupted supply chains at different points, displacing empty containers and becoming one of the pinch points in international trade.

Ocean freight capacity more generally has also reached the limits of what it can deliver while health measures remain in place at ports. The growth in traffic has reached a point where globally, the majority of ships are missing scheduled arrival times, and late ships are being delayed for around a week before new slots open up for them. Reflecting the intense competition for capacity, shipping costs have been growing strongly since autumn 2020, adding pressure on input prices.

Among widespread shortages and price rises, metals stand out

Shortages are rising across sectors, including rubber producers, plastics products, electrical equipment, motor vehicles, wood, and computers and electronics. And among rises in the prices of many inputs, industrial metals stand out with more than 70% increase relative to pre-pandemic levels.

Like other commodities, a combination of pandemic and non-pandemic-related factors are at play. Mine closures in the initial round of lockdowns in 2020 led to a temporary pause in supply, which then resumed but faced unprecedented demand as inventories were rebuilt alongside serving current demand. That demand includes manufacturing, hit less than services during the pandemic, and infrastructure and energy-transition related projects.

The pauses in production which have driven some input prices so high are being magnified by the poor performance of supply chains. Both metals and lumber prices have come down from recent peaks, as falls in supply are replaced by more normal rates. However, new price spikes are possible into 2022 during the next phase in the global recovery, while supply chains and inventories offer little chance of catching up after setbacks.

Shipping costs to remain higher

Globally, capacity on major shipping routes has recovered to levels before the major lockdowns in 2020, although blank sailings (container ship journeys being scheduled but then cancelled) continued to cut 10% of scheduled capacity through the first half 2021. On current plans, cancelled sailings will come down to around 1% in 3Q. But cancellations are partly a response to delays, so the picture may still change.

A flood of new container capacity will ease price pressures, but not before 2023. Having enjoyed outstanding financial results during the pandemic, shipping companies have placed record levels of new orders for container vessels during 2021. But the companies also seem to have learnt how to manage capacity better in their alliances. They may continue to take capacity out of the system at short notice, reducing the price-dampening impact of new capacity coming onstream.

Pressure on ocean freight capacity will rise further as trade partners gradually recover from the effects of the pandemic at different speeds. But uncertainty about the recovery, including the possibility of new port closures, may well continue to exacerbate the displacement of empty containers and delays for key inputs.

Warning signs for global supply chains, will businesses reshore?

Costs have been rising before the pandemic for industries making intensive use of foreign inputs, thanks to increases in trade barriers, which aren’t going away any time soon. But the ongoing disruptions to supply have brought the risks of using global supply chains into focus, with a new push to develop domestic capabilities, especially in technology, and create a degree of independence in the supply of essential medicines and technology goods.

The pandemic has seen a rise in trade barriers affecting food and medical products and subsidies to domestic industries across a wide range of sectors. These measures were primarily introduced as an emergency response. But they have largely remained in place as the pandemic has progressed. The measures taken during the pandemic add to the difficulties of access to foreign markets that had been rising before the pandemic, including during the US-China trade war.

But a global effort to dismantle trade barriers is not on the cards. Instead, progress is unlikely to go much beyond piecemeal progress within the context of bilateral talks, such as the suspension of tariffs in the Airbus-Boeing dispute between the EU and the US. Policy effort in China, the EU and the US seems instead to be focusing on reshoring in key sectors, likely through subsidies, which in the case of the US especially have been supercharged by large fiscal stimulus plans.

One consequence of more support for domestic production could be to bring down the relative costs of producing locally, which may tilt the balance for some supply chains to be brought home. Still, reshoring is hard to do and not necessarily the right move for increasing resilience.

Input shortages to continue into 2022

With input shortages to continue into 2022 and container prices remaining elevated into 2023, the supply of inputs is likely to be one of the major challenges for industrial production. Even as some frictions ease as the recovery progresses, trade barriers have risen.

Add to that a policy environment increasingly geared towards reshoring and domestic production, and it becomes clear that while global demand will continue to support industrial production globally, firms face a difficult and more costly environment to get the inputs they need for production.

Download

Download article

30 July 2021

When doves cry This bundle contains 6 articles"THINK Outside" is a collection of specially commissioned content from third-party sources, such as economic think-tanks and academic institutions, that ING deems reliable and from non-research departments within ING. ING Bank N.V. ("ING") uses these sources to expand the range of opinions you can find on the THINK website. Some of these sources are not the property of or managed by ING, and therefore ING cannot always guarantee the correctness, completeness, actuality and quality of such sources, nor the availability at any given time of the data and information provided, and ING cannot accept any liability in this respect, insofar as this is permissible pursuant to the applicable laws and regulations.

This publication does not necessarily reflect the ING house view. This publication has been prepared solely for information purposes without regard to any particular user's investment objectives, financial situation, or means. The information in the publication is not an investment recommendation and it is not investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Reasonable care has been taken to ensure that this publication is not untrue or misleading when published, but ING does not represent that it is accurate or complete. ING does not accept any liability for any direct, indirect or consequential loss arising from any use of this publication. Unless otherwise stated, any views, forecasts, or estimates are solely those of the author(s), as of the date of the publication and are subject to change without notice.

The distribution of this publication may be restricted by law or regulation in different jurisdictions and persons into whose possession this publication comes should inform themselves about, and observe, such restrictions.

Copyright and database rights protection exists in this report and it may not be reproduced, distributed or published by any person for any purpose without the prior express consent of ING. All rights are reserved.

ING Bank N.V. is authorised by the Dutch Central Bank and supervised by the European Central Bank (ECB), the Dutch Central Bank (DNB) and the Dutch Authority for the Financial Markets (AFM). ING Bank N.V. is incorporated in the Netherlands (Trade Register no. 33031431 Amsterdam).