Four charts show the risk of a ‘no deal’ Brexit to the UK economy

Talk of a 'no deal' Brexit is ramping up as UK lawmakers remain divided on future European trade. We still think it's more likely that an agreement will be struck to prevent the UK from crashing out of Europe without a deal, but if we're wrong, here are a few key ways the economy could be hit

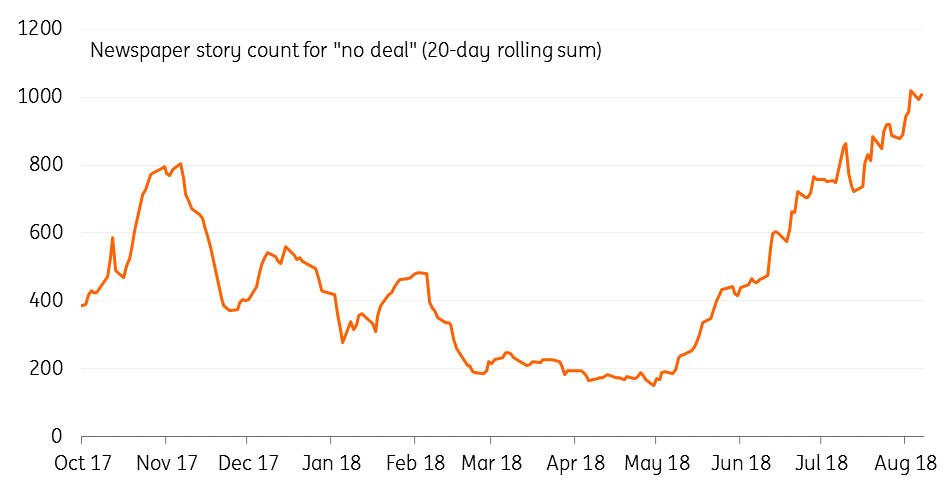

Talk of ‘no deal’ is ramping up significantly

There are 233 days to go until Brexit and with negotiations stuck in deadlock, talk of 'no deal' is ramping up. The number of news stories discussing the topic has spiked, while Google searches for 'no deal Brexit' have surged. This comes as the UK government prepares to outline its contingency preparations for a possible hard exit next March, something which International Trade Secretary Liam Fox suggested over the weekend now has a 60% probability of occurring.

At this stage, we still think it's more likely that the UK and EU forge an agreement to avoid the hardest of Brexit scenarios, allowing the transition period to begin after March 2019. But the situation is highly uncertain and if we're wrong, the economic impact could be significant. Leaked UK government forecasts earlier this year suggested that without a deal, the economy could be 8% smaller over a 15-year horizon relative to current projections.

There are many potential ways the economy could be hit if 'no deal' happens, but here we take a look at a few of the major factors at play.

People have kept jobs so far - but that could change

It's been a tough time for retailers since the Brexit vote. Consumers cut back as import prices rose, while higher minimum wage costs and increased business rates have placed heavy pressure on margins. But while households have become more frugal, spending hasn't completely collapsed, and the economy has so far avoided a recession. There are several potential reasons for this, but the fact that most people have kept their jobs is undoubtedly one of the most influential.

Employment has increased by 2% since June 2016, compared to sharp and prolonged declines during the previous two notable economic downturns. And whilst overall consumer confidence remains depressed, unemployment expectations remain very low by historical standards.

But this sentiment could face a serious test when the government begins to formally outline its 'no deal' preparations later this month. Press leaks so far suggest the proposed measures range from food/medicine stockpiling to mooring electricity generators off the coast of Northern Ireland. Having faced months of criticism for lack of 'no deal' preparation, the government is trying to demonstrate it's serious about potentially walking away from talks. You could also make the argument that by talking up the risks of 'no deal' now, the government may be attempting to get Brexiteer and opposition MPs to think twice about rejecting the final deal May agrees in Brussels.

But this could prove to be a risky approach. After all, food stockpiling is fairly unprecedented in a modern developed economy and it's not clear how people would react. Admittedly, we doubt many consumers are that fazed by the threat of 'no deal' at this stage. But as time goes on, it's not unimaginable that a few dramatic newspaper headlines could see consumers cut back on spending further, particularly if individuals begin to become more concerned about job security.

'No deal' could create major congestion – and not just at Dover

There's little doubt a 'no deal' scenario would create significant disruption at borders, and the obvious point of friction is Dover. Much of the UK's trade with Europe is done by lorry via the Channel, and the British Freight Transport Association has estimated that even two-minute delays at customs could generate 29-mile queues back up the motorway into Kent.

But frictions at the UK's other major ports could be equally damaging. To understand why, consider the Port of London, the UK's third largest port by gross tonnage. Here 58% of total inbound and outbound traffic is to/from either the Netherlands or Belgium (it's a similar story at the UK's other big ports too). This is because the big Dutch/Belgian ports of Rotterdam, Antwerp and Zeebrugge are big re-exporters. Goods arrive from across the globe, and are put on smaller ships and transported to the UK (and vice versa).

But while the UK predominantly trades with a fairly narrow set of European ports, the same is not true the other way around. By our calculations, 70% of the UK's marine trade with Europe is spread across no less than nine different British ports. Delays at any one of these terminals could have serious ramifications for supply chains on both sides of the channel, as well as the smooth running of Northern European ports.

70% of the UK's marine trade with Europe is spread across no less than nine different British ports

This is, of course, a bit of simplification. Different ports specialise in different goods, some of which are typically subject to less regulatory/customs scrutiny than others. In any case, the UK may end up keeping its borders open in the immediate aftermath of a 'no deal' Brexit anyway.

That said, as our International Trade team points out, the UK's WTO obligations potentially mean it would have to extend this zero-tariff treatment to all its global imports, which could complicate future trade negotiations (because these conditions can't really be improved upon).

In any case, whether the EU would be so flexible is unclear. Brussels is already wary of the UK's customs approach, having imposed a €2 billion fine on the British government last year for failing to crack down on illegal Chinese imports. It therefore might not take long before the EU seeks to tighten up on border checks after Brexit.

Tighter financial conditions would cause problems on both sides of the channel

Financial conditions have been another key insulating factor for the UK economy since Brexit. Unlike earlier in the post-crisis years, credit and interbank spreads remained calm, while the initial spike in equity/currency volatility quickly subsided.

But the situation could look very different in the event of 'no deal'. The sudden elevation in uncertainty would likely spark a severe period of risk-off, where the flight to safety could see credit spreads widen and volatility spike. Even before March 2019, if the perceived risk of 'no deal' continues to rise, financial conditions could start to tighten well in advance of the EU exit date.

There are also major question marks over what would happen to financial passporting. Some kind of emergency stop-gap solution is not implausible (the UK has proposed a "temporary permissions regime") - and the Bank of England is confident that financial firms have the capital to insulate themselves against the 'no deal' risk. However, the possibility of a sudden change in market access could see banks significantly tighten up on credit availability for households and businesses, amplifying the negative growth impact of lower confidence and production/supply chain disruption.

Of course, the one possible offset in all of this would be the pound. Sterling would likely plunge in the event of a 'no deal'. But while the theory says this should help cushion exporters, we aren't so convinced. Given the complexity and globalised nature of supply chains, the impact of border frictions on just-in-time production is likely to far outweigh changes in pricing for exporters. After all, many UK firms that trade exclusively with Europe may have never had to deal with the practicalities of trading on WTO terms. Tariff schedules are typically very complex, and if firms get it wrong, dispute resolution can take many months.

This means that the primary effect of the weaker pound would likely be sharply higher prices for consumers.

So will a 'no deal' Brexit actually happen?

In the end, the answer to this question probably boils down to whether parliament accepts the withdrawal agreement Prime Minister Theresa May agrees with the EU.

The major sticking point in talks is the Irish backstop - the legally-binding agreement to maintain a frictionless border between Northern Ireland and the Republic. So far, the issue has proven highly contentious, not least because the UK government fears it could create regulatory barriers within the UK's own internal market.

But as 'no deal' fears mount, the EU appears to be offering an olive branch. Michel Barnier has hinted that the backstop could be "de-dramatised", potentially by making efforts to reduce infrastructure at the border, and even possibly reducing the role of the ECJ.

Whether this will be enough to convince UK lawmakers is unclear. But as March 2019 draws nearer, Brexiteer MPs may be less inclined to vote against the overall withdrawal agreement in parliament. Rejecting this deal could raise the odds of another election, an extended article 50 period, or possibly even a second referendum - all of which are highly undesirable for Brexiteers because they would increase the risk of there being no Brexit at all.

So while the outlook for Brexit over the next few months is incredibly uncertain, we still suspect the most likely outcome is that a mixture of fudge and "de-dramatised" language sees the withdrawal agreement passed by a majority of UK MPs, allowing the transition period to commence.

Download

Download article10 August 2018

In case you missed it: Emerging markets in turmoil This bundle contains {bundle_entries}{/bundle_entries} articlesThis publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more