Covid-19 uncertainties to weigh on bank regulation in 2021

The Covid-19 pandemic has led to a flood of regulatory responses in order to mitigate the impact of the crisis on households, corporates and banks. All these measures have guided banks well through the first storms of the Covid-19 crisis. The major question now is to what extent banks will still be able to rely on these temporary provisions in 2021

The Covid-19 regulatory backdrop

To what degree banks would still be able to reap the benefits from the current constructive regulatory backdrop in 2021, should pretty much depend on how the Covid-19 situation evolves. If the virus rears its head again with a vengeance, resulting in renewed lockdowns and economic pressures, the odds are high that governments and central banks will continue to do their utmost to navigate the crisis.

In the recent October communiqué, G20 finance ministers and central bank governors even confirmed their “determination to continue to use all available policy tools as long as required to safeguard people’s lives, jobs and incomes, support the economic recovery, and enhance the resilience of the financial system, while safeguarding against the downside risks.”

Major policy responses in light of the Covid-19 crisis

The European Banking Authority postponed the EU-wide bank stress test to 2021 to alleviate the operational burden for banks in 2020 considering the Covid-19 challenges.

In March 2020, global banking regulators decided to postpone the Basel-III reforms until January 2023, also to give banks and regulators access to sufficient resources to adequately respond to the coronavirus pandemic.

The Capital Requirement Regulation quick fix which came into force in June 2020 moved forward certain capital benefits that would otherwise apply as of 28 June 2021. This included the revised treatment of software assets, provisions on loans backed by pensions or salaries, the revised supporting factor for SME exposures and the new supporting factor for infrastructure finance.

The CRR quick fix also temporarily, for a period of seven years, exempts Covid-19 loan guarantees from CET1 NPE adjustment. Besides, it also extends the transitional period related to expected credit loss provisioning under IFRS9 by two years. Meanwhile, the derogation to exempt central bank reserves from the leverage ratio exposure measure was moved forward by a year, while adjustments were made to the offsetting mechanism to make the use of the exemption less penalizing in terms of additional leverage ratio requirements.

The EBA issued guidelines ensuring that Covid-19 related payment holidays would not automatically result in a reclassification of exposures as forbearance or defaulted. In September, the EBA announced plans to phase out its guidelines in accordance with the end of September 2020 deadline. The regulatory treatment set out in the guidelines will continue to apply however to all eligible payment holidays granted prior to 30 September 2020.

That aside, the ECB has implemented several measures to soften the burden on banks related to the Covid-19 crisis. These include measures to ease the capital requirements for banks by allowing them to temporarily operate below the level of capital defined by the pillar 2 guidance (P2G), the capital conservation buffer (CCB) and the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR). The ECB also recommended banks not to pay dividends at least until the end of this year, and the liquidity support offered to banks against very favourable terms under the TLTRO-III operations. The use of the latter has among others been facilitated by several collateral easing measures.

This means that next year’s focus will largely be on those measures that were put in place temporarily to optimise the conditions for banks to deal with the Covid-19 crisis. Part of these temporary measures, such as the exemption of central bank reserves from the leverage ratio, will end next year. This raises the question as to whether a deterioration of the coronavirus situation would prompt central banks to keep them in place for a longer period of time than initially intended. Besides, some important regulations such as the Basel-III reforms have been postponed to give banks the extra time and resources to cope with the pandemic. If the regulatory pipeline isn't further moved forward, 2021 should remain a very active year as far as banking sector regulation is concerned. In the remainder of this section, we touch upon a few examples.

Stress testing the Covid-19 fallout

The yearly stress testing exercise by the EBA was not organized in 2020 in the middle of the Covid-19 pandemic. Instead, the EBA indicated that the next round of bank stress testing will be organized in 2021. The exercise should be launched at the end of January 2021, with the results scheduled to be published at the end of July 2021. The exercise will entail 51 banks across the European Union covering 70% of the sector, in line with the plan for the 2020 testing round. The 2021 stress test will be based on the methodology and design put together for the 2020 test exercise, but adjusted for certain factors including debt moratoria, public guarantees and changes in regulation.

The EBA bank stress tests entail a substantial amount of valuable information allowing market participants to assess the viability of the banking sector and individual banks. We consider the stress testing exercise an important addition to the financial reporting of banks, even though the availability of comparable data on a bank-to-bank basis has increased substantially since the financial crisis. The EBA transparency exercises particularly allow markets to stress bank financials in their own scenarios already. With the 2021 stress testing exercise, the market interest will likely be especially focussed on the possibility of obtaining comparable debt moratoria and guarantee data across the EU.

MREL – What’s in store for banks?

While the effects of Covid-19 have hit European economies, the impact on the banking sector has so far been limited by the substantial measures taken by central banks and governments. As we expect the loan quality of banks to weaken with the expiring moratoria, banks with already poor profitability and limited capital buffers are most at risk. The longer the stress on the economies and banks lasts, the harsher the effects will be. Resolvability of the weakest links may yet be tested.

MREL requirements (Minimum Requirements for own funds and Eligible Liabilities) were created to ensure that banks maintain sufficient eligible instruments to allow for the implementation of the applicable resolution strategy in case of need. On top of the subordination requirement, the location of eligible liabilities also plays a role here. The aim is to prevent the need for utilising public funds for a bailout.

The impact on the banking sector has so far been limited by the substantial measures taken by central banks and governments

The Single Resolution Board (SRB) is expected to communicate to banks in early 2021 the level of MREL they are expected to hold in line with the 2020 resolution planning cycle. That planning cycle communication is expected to include two binding MREL targets, an intermediate one to be met by 1 January 2022, and the final one to be met by 1 January 2024.

The MREL decisions are expected to reflect the changed capital requirements and also to take into account the effect of Covid-19 on the banking system. The SRB has indicated that it will use the flexibility in the regulatory framework, such that short term MREL constraints will not prevent banks from lending to businesses and households. Therefore, if the Covid-19 situation and the economic outlook were to substantially weaken, we would expect this to be reflected in the resolution planning as a longer transitioning time given to banks.

Postponement of the Basel-III reforms – giving banks a one year breather

The Covid-19 outbreak has prompted global banking regulators on 27 March 2020 to postpone the Basel-III reforms (often dubbed as Basel IV) from January 2022 until January 2023, to spare banks and regulators the resources to adequately respond to the coronavirus pandemic. The transitional arrangements for the much-debated output floor were also extended by a year to 1 January 2028. This means that the standardised output floors will now be phased in from 50% in 2023 to 72.5% by 2028.

Meeting the January 2022 deadline was always seen as challenging

For Europe, meeting the January 2022 deadline with the CRD6/CRR3 package implementing Basel IV was already always seen as challenging, given the importance and far-reaching impact of the reforms for European banks. However, instead of publishing its CRD6/CRR3 proposals in June 2020, the European Commission should now probably publish them in the first half of 2021. This raises the question of whether this could delay the CRD6/CRR3 package even until 1 January 2024 instead of 1 January 2023.

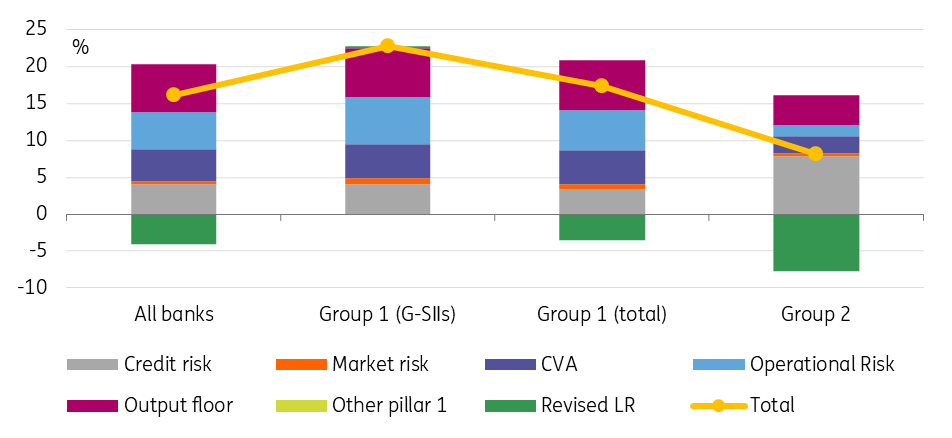

The beneficial side effect of such a delay would be that European banks will be granted more time to meet the stricter capital requirements. The European Banking Authority (EBA) estimated in April this year that European banks would need €21.1bn of additional Tier 1 capital to comply with the new Basel framework. A further delay would give banks more time to attract or free up the additional capital.

The increase in the capital requirements that banks face under Basel IV is among others the result of the introduction of the output floor for banks using internal models, which is set at 72.5% of the capital requirements based on the standardized approach. The output floor is particularly penalising in conjunction with the stricter risk weight requirements under Basel IV for specialised lending, unrated corporate exposures or higher LTV mortgage loans under the standardised approach. In addition, banks are also no longer allowed to use the advanced Internal Ratings-Based approach for all exposures. For instance, for exposures to large corporates and banks, banks would have to apply the foundation IRB.

According to EBA estimates particularly the largest European banks are impacted by the increased capital requirements, meaning these banks will also be the ones benefitting the most from the extra time granted by the postponement of Basel IV.

Change in T1 minimum required capital due to Basel- III reforms by 2028

Knock-on effects for banks

The postponement of the Basel-III reforms also has certain side effects for banks on the bond market funding side. For example, the reforms provide for a more favourable risk weight treatment for covered bonds on a global level if the bonds meet certain minimum requirements. This will now be delayed until 1 January 2023. Within the EU, covered bonds already benefit from a more favourable risk weight treatment under the Capital Requirments Directive, but this applies only to covered bonds issued by banks located within the EEA. The third-country equivalence discussion was also left outside the scope of the European Covered Bond Directive that entered into force in January this year. Instead, the European Commission will publish a report on third-country equivalence, potentially together with a legislative proposal on how it should be introduced, by 8 July 2024 at the latest. As such, the delay of the Basel-III reforms is of more importance to the introduction of a favourable risk weight treatment for covered bonds for banks outside the EU, than it is for the treatment of third-country covered bonds within the EU.

Other changes to the capital requirements of bank bonds that will be delayed by a year include, for example, the change in capital requirements for banks under the standardised approach for preferred senior unsecured bonds issued by other financial institutions. Namely credit quality step (CQS) 2 bonds (i.e. those with a second-best A- to A+ rating) will get a 30% risk weight under the standardised approach instead of the current 50%. For bail-in senior unsecured and T2 instruments the risk weight treatment would become 150% and for AT1 instruments basically 250%, where under the current CRR the risk weight treatment is a similar 100% (non-significant investment) as for AT1 instruments to the extent that they fall below the 10% CET1 threshold for non-significant investments. T2 and AT1 instruments have a 250% risk weight where they are significant investments but fall below the applicable CET1 threshold. Holdings above the applicable CET1 thresholds would also under Basel IV still have to be deducted correspondingly from the own issued eligible liabilities and capital instruments.

Digital and data regulation: Many initiatives, but limited impact in 2021

On the digital and data front, a lot is going on that will influence banks in the future. The European Commission is preparing its Digital Services Act. Regulation of digital platforms with a “gatekeeper” function is to be intensified. For banks, this may be some welcome support in their increasing competition with big-tech platforms. The problem for banks is that what is core business for them, may only be a peripheral service offering for big-tech platforms, helping to make those platform more attractive for end-users. The growing dominance of platforms increases their market power. Policymakers are considering tools to safeguard the diversity of digital services, so customers retain a choice. This should help banks as well, though the main risk for them in the digital era remains that they lose primary access to customers, becoming dependent on third-party platforms for that.

Furthermore, European Commission proposals are expected in 2021 moving from open banking (PSD2) towards open finance. In other words, a broadening of portability for financial data. This would enhance opportunities to build one-stop-shop financial platforms, thus intensifying competition, and putting the most digital-savvy banks and fintechs at a further advantage.

It should be noted that both on the digital regulation and data front, Brussels will still be in the proposal discussion phase in 2021. The impact of these initiatives will not be felt until (well) after 2021. They are important though for the medium to long term strategic direction banks can take.

The political will to create a central bank digital currency seems strong

A third relevant item is the exploration of a digital euro by the ECB. While the advantages of a retail central bank digital currency from a user perspective in a European context appear limited, the political will to create one nonetheless seems strong, mainly for geopolitical reasons. For banks, it may mean a partial loss of deposit funding and intensified competition by non-bank providers of digital euro wallets. But this too is a long-term project. Remember that the People’s Bank of China started studying CBDC in 2014, and only moved to pilot a digital currency this year. Surely other central banks can move faster now, building on research and experience that has already built up, but tinkering with the fundaments of the monetary and financial system is not something central banks do lightly. The ECB will decide on further exploration in mid-2021, so it may well be 2024 or later before a digital euro is widely available, if at all.

Leverage ratio requirements – what to expect from the CB reserve exemption?

On 28 June 2021 the leverage ratio requirements for banks will become binding. Around that time the ECB will also decide if the temporary exemption of central bank reserves from the leverage ratio exposure measure is extended by another year. This could have consequences for the TLTRO-III repayment behaviour of banks as of September next year, albeit probably only to a limited extent as most banks are well-positioned to meet the leverage ratio requirements.

The CRR leverage ratio provisions provide a discretion to temporarily exclude central bank reserves from a bank’s leverage ratio calculation under exceptional circumstances. This exemption can be granted by the supervisory authority for a period of maximum one year, under the condition that the exclusion is fully offset by a mechanism that proportionately increases the bank’s leverage ratio requirement (the offsetting mechanism).

Under the CRR quick fix of 24 June 2020, banks were already given the option to exclude central bank exposures (ie coins and banknotes and deposits held with the central bank) from their total exposure measure until 27 June 2021. The offsetting mechanism was also modified to ensure the effectiveness of the use of this exclusion option. Banks using the discretion would still be required to calculate an adjusted leverage ratio, but now only at the moment that the discretion is exercised. The adjusted leverage ratio would then not change anymore for the period during which the discretion is effective.

These measures were taken to ensure that leverage ratio considerations wouldn't stand in the way of banks from using the ECB longer-term refinancing operations (ie the TLTRO-III) as a consequence of a parallel rise in their central bank reserves. The option was granted however, subject to the condition that the competent authority would first confirm the existence of exceptional circumstances justifying such an exclusion in light of monetary policy implementation. On 17 September 2020, the ECB acknowledged the existence of exceptional circumstances for the whole euro area, allowing for the temporary exclusion of central bank reserves from the leverage ratio.

While the 3% leverage ratio requirement only becomes binding on 28 June 2021, banks already disclose their current leverage ratio. Hence, the measures taken by the CRR quick fix this year already served to signal an improvement in the current leverage ratio of the banks. The ECB estimated that based on data from the end of March 2020, the exclusion would lift the aggregate leverage ratio of 5.36% by 0.3ppt. Besides, in its September 2020 press release, the ECB also pointed out that for globally systemically important banks (G-SIBs) the measure provides relief under their already binding total loss-absorbing capacity (TLAC) requirements.

The exemption from the exposure measure is currently applicable until 27 June 2021. The ECB will then decide if it wishes to extend the exclusion beyond June 2021, ie once the 3% leverage ratio will become binding. This would require a certain upward recalibration of the leverage ratio requirement though. That said, besides the implications of such a decision on the reported level of the leverage ratio, or in terms of any loss-absorption relief, this decision could also be of relevance for the TLTRO-III.

Namely, banks have the first opportunity to repay part of their TLTRO-III drawings early as of September next year. If the ECB decides not to extend the measure by another year, this might impact their TLTRO prepayment behaviour. For some banks, this could be a reason to reduce their excess liquidity, particularly considering that the favourable -1% interest rate term under the TLTRO-III operations will have ended by then.

The ECB’s decision to use the discretion by another year will obviously depend on the duration of the exceptional circumstances as a result of the coronavirus pandemic. If a phase of new lockdowns would result in renewed pressure on European economies and banks, the odds indeed become higher that the ECB will extend the leverage ratio exemption.

NSFR - A more important consideration for banks as of mid 2021

In June 2021 the Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) will become binding to banks. This means that banks need to have sufficient stable funding available to cover their stable funding requirements over a one year period. Once binding, the NSFR will probably become a more important factor for banks to consider in their (re)financing decisions.

This means that the NSFR will also have a greater weight in the decision by banks to repay or refinance their TLTRO drawings. The drawings by banks under the 3yr TLTRO-III operations do count as stable funding until one year ahead of their expiration date. However, in the event of the previous TLTRO-II operations, the (partial) loss of NSFR recognition of the applicable tranches a year ahead of maturity, was by some banks not deemed that important as the NSFR was still not binding in Europe. Other banks did already take the impact of the expiration date of the TLTRO-II tranches on the reported NSFR into account in the decision to early repay or refinance their drawings.

Banks may also feel more pressure to refinance their bonds at least a year ahead of maturity

Once the NSFR becomes binding, banks may also feel more pressure to refinance their bonds at least a year ahead of maturity. Besides, the NSFR regulation explicitly states that institutions have to take into account existing options in determining the residual maturity of a liability. For options exercisable at the discretion of the institution, the reputational consequences of not exercising the option have to be considered. For AT1 and T2 bonds with embedded call options, the NSFR regulation is explicit that the bonds would lose their 100% NSFR recognition one year ahead of the call date.

The reasons for banks to participate in the TLTRO operations

However, banks nowadays also regularly use call dates one year ahead of maturity for their bail-in senior bonds to be able to repay the bonds once they are no longer MREL eligible. One could argue that if the bank is determined to use the call option, the bond should lose (part of) its NSFR recognition in the year before the call date (ie potentially resulting in a refinancing need two years ahead of the bond’s final maturity date).

The same should arguably apply to a bank’s TLTRO drawings should the bank decide to early repay part of its TLTRO drawings on any of the relevant early repayment dates. The ultimate impact of NSFR considerations on the TLTRO-III repayments may ultimately prove to be modest though, as meeting regulatory or supervisory requirements was never the most important reason for banks to participate in the TLTRO operations.

Tags

Banks Outlook 2021Download

Download article

30 October 2020

Banks Outlook 2021 This bundle contains 9 articlesThis publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more